The art of adaptation: from 'Story of Your Life' to 'Arrival'

Hollywood has always been in the adaptation business. It used to be that producers plundered Broadway and the works of classic literature for material. Nowadays the emphasis has shifted to comic books and video games, but in the end little has changed; just try to think of the last movie you saw that wasn’t based on something else. So, it’s worth asking: what exactly constitutes a good adaptation?

This was one of the many questions I was left pondering after seeing the film Arrival, which is based on Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life.”

The first time I read “Story of Your Life” I wasn’t sure it could be adapted into any medium, let alone a film. It’s intricately structured, intellectually dense and narratively ambitious, utilizing everything from variational physics to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of language to tell the story of first contact between humanity and an alien species. Despite being anchored in a tender, heartbreaking mother-daughter relationship, it’s easy to see why this isn’t typically the kind of material that makes it to the big screen.

And yet not only did Arrival make it to the big screen, it manages to render the complexity of “Story of Your Life” accessible, remain true to the story’s alternately cerebral and humanistic tone and expand the scope of the story in ways that feel logical, exciting and earned. In other words, Arrival is not only a fantastic movie, it’s a fantastic adaptation.

It’s difficult to explore the ways Arrival adapts “Story of Your Life” without divulging a few spoilers, but I’ll try to keep the plots of the story and film as secret as possible.

Both open with the inexplicable arrival of an alien species at apparently random points across the globe. Louise Banks, a linguistics scholar and professor (played by Amy Adams in the film), agrees to help an American team attempt communication with the aliens. Along the way she’s accompanied by military overseers and a physicist named Donelly (played by Jeremy Renner in the film).

Notwithstanding the similarity of their premises, the story and the film are different beasts right from the beginning. The story opens with Louis addressing her daughter, recounting “the most important moment in our lives.” It takes a while to get your sea legs with the story; for reasons that only become clear at the end, Chiang regularly changes tense, sometimes within the same sentence, resulting in passages like: “I remember one afternoon when you are five years old, after you have come home from kindergarten. You’ll be coloring with your crayons while I grade papers.”

These sections alternate with the story of Louise and Donelly searching for a way to communicate with Earth’s alien visitors, who are described as looking “like a barrel suspended at the intersection of seven limbs,” and are therefore dubbed “Heptapods.”

The film, by contrast, begins with a montage that sketches out the the life of Louise’s daughter from birth to death. This poignant opening casts a melancholic shadow over the rest of the film, which details Louise and Donelly’s interactions with the Heptapods. Then, at the halfway point, Louise begins to experience what seem like flashbacks to moments with her daughter. Suffice it to say, the truth is far more complicated – as it is in the story.

These differing structures nonetheless end up achieving the same effect. The alternating framework of the story (along with the constantly shifting tenses) allows Chiang to establish two central mysteries, one about deciphering the Heptapods’ language and the other about the nature of Louise’s relationship with her daughter. Arrival, meanwhile, uses the language of film editing, cutting between two timelines, to establish the same mysteries as the story.

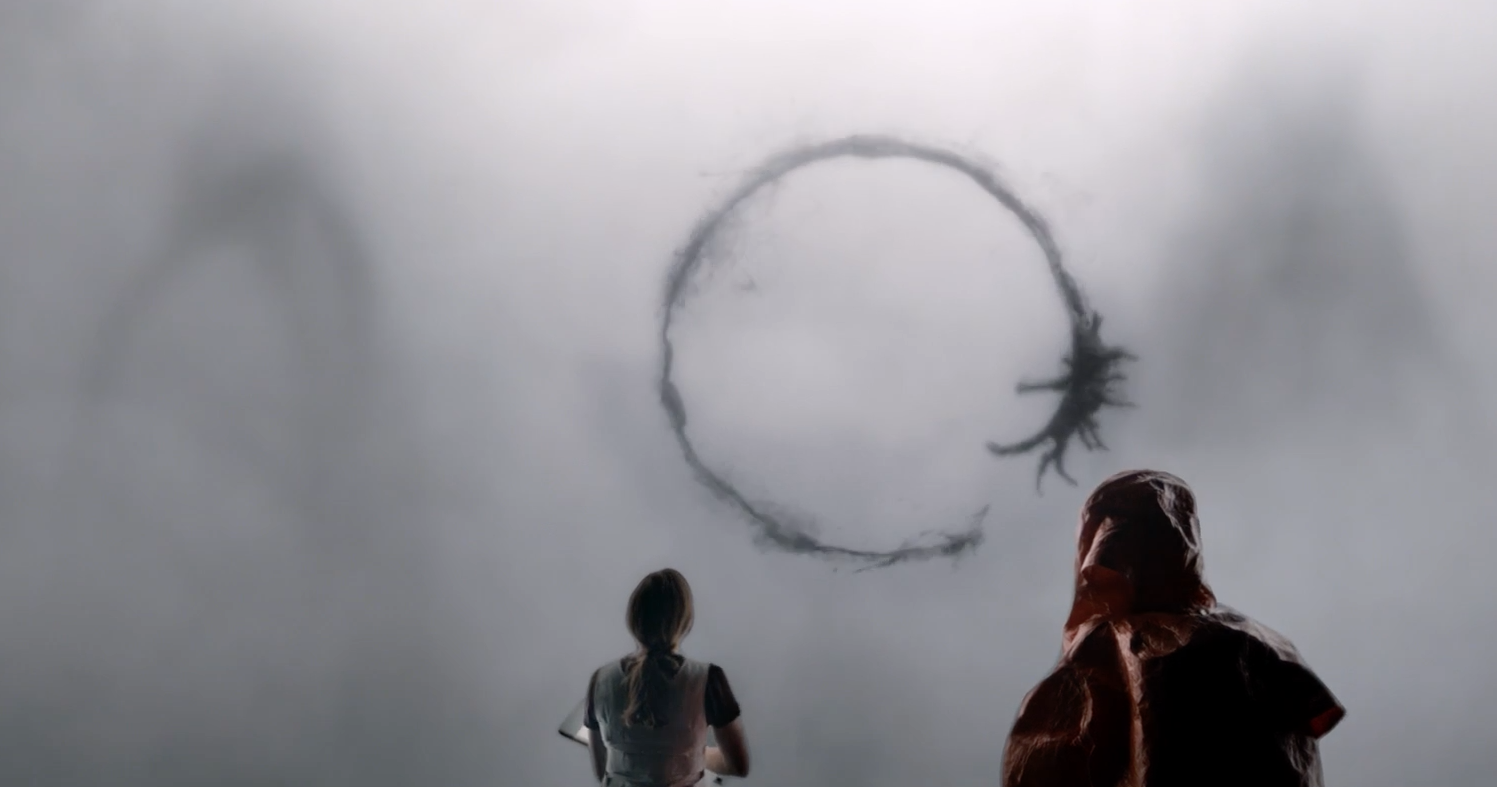

Rather than simply imitate the story, though, Arrival finds skillful ways to expand the scope, imbuing the same basic material with heightened stakes and a sense of cosmic grandeur. For instance, in the story the interactions with the aliens take place inside a tent where a “looking glass…[with] a semicircular mirror over ten feet high and twenty feet across” divides human from Heptapod. The film, however, moves these interactions to the Heptapods’ massive, seed-shaped vessel, which hovers majestically above a desolate landscape.

Nor does the film shy away from introducing entirely new narrative developments. There’s a more urgent sense of conflict among the various teams across the globe working to decipher the Heptapods’ language. There’s also greater tension between Louise and Donelly's more measured, scientific perspectives and the imperatives of the military – a tension that escalates as the film draws near its conclusion.

In a less artful film, these expansions might ring false, yet another example of Hollywood messing with a good thing by piling on needless complications. Instead, screenwriter Eric Heisserer and director Denis Villeneuve consider what is left unsaid or unexplored in the story and use these elisions as opportunities to put their own spin on the story’s core narrative.

And this approach is what makes Arrival such a good adaptation. It’s all too common to frame an adaptation’s success purely in terms of fidelity to the source material. But movies are a distinct art-form, just as short stories are a distinct art-form, and what works in one isn’t guaranteed to work in the other.

So rather than approach an adaptation with the goal of faithfully recreating the source material, it’s far better, in my opinion, to view adaptations as opportunities for transformation. The filmmakers behind Arrival understand this concept, retaining the mind-altering ideas and contemplative tone from “Story of Your Life,” while simultaneously creating something new and vibrant and utterly itself.

Now if only the rest of Hollywood would get the message.