Home on the range

Agriculture remains the heart of Adams County

Step outside in Adams County, Colo., and you’ll likely see a population on the rise, complete with construction and new housing developments. One of the fastest-growing communities in the state, Adams County has experienced a 21.4 percent population growth over the past 10 years. Although the county continues to experience all of the economic and social shifts that come with rapid growth, agriculture remains at the heart of the community’s identity.

As one of the only counties in metro Denver with an active farming community, Adams County’s relationship with the land remains strong. Farm land accounts for more than three-quarters of all the land in Adams County, including the almost entirely agricultural communities of Bennett and Strasburg. Adams County, in other words, is where you’ll find the farms that set up shop at Front Range farmers’ markets.

“Adams County is an agricultural community – period,” says Clifford Lushbough, chairman at the Adams County Historical Society.

Lushbough, along with the other members of the Adams County Historical Society, look at this connection as a way of connecting with the past to understand the present. Both the Adams County Historical Society and the Commerce City Historical Society spend time collecting the stories of this longstanding agricultural community to help give newcomers a lens to understand the history and future of the area.

“This is how we’re documenting history,” says Debra Bullock, secretary and treasurer of the Commerce City Historical Society. “We find people who lived it, and we’re having them document it for us. And that’s important, because without it, we wouldn’t know that story.”

With research help from these local historical groups and longtime residents, below are two stories that shaped Adams County’s agricultural landscape.

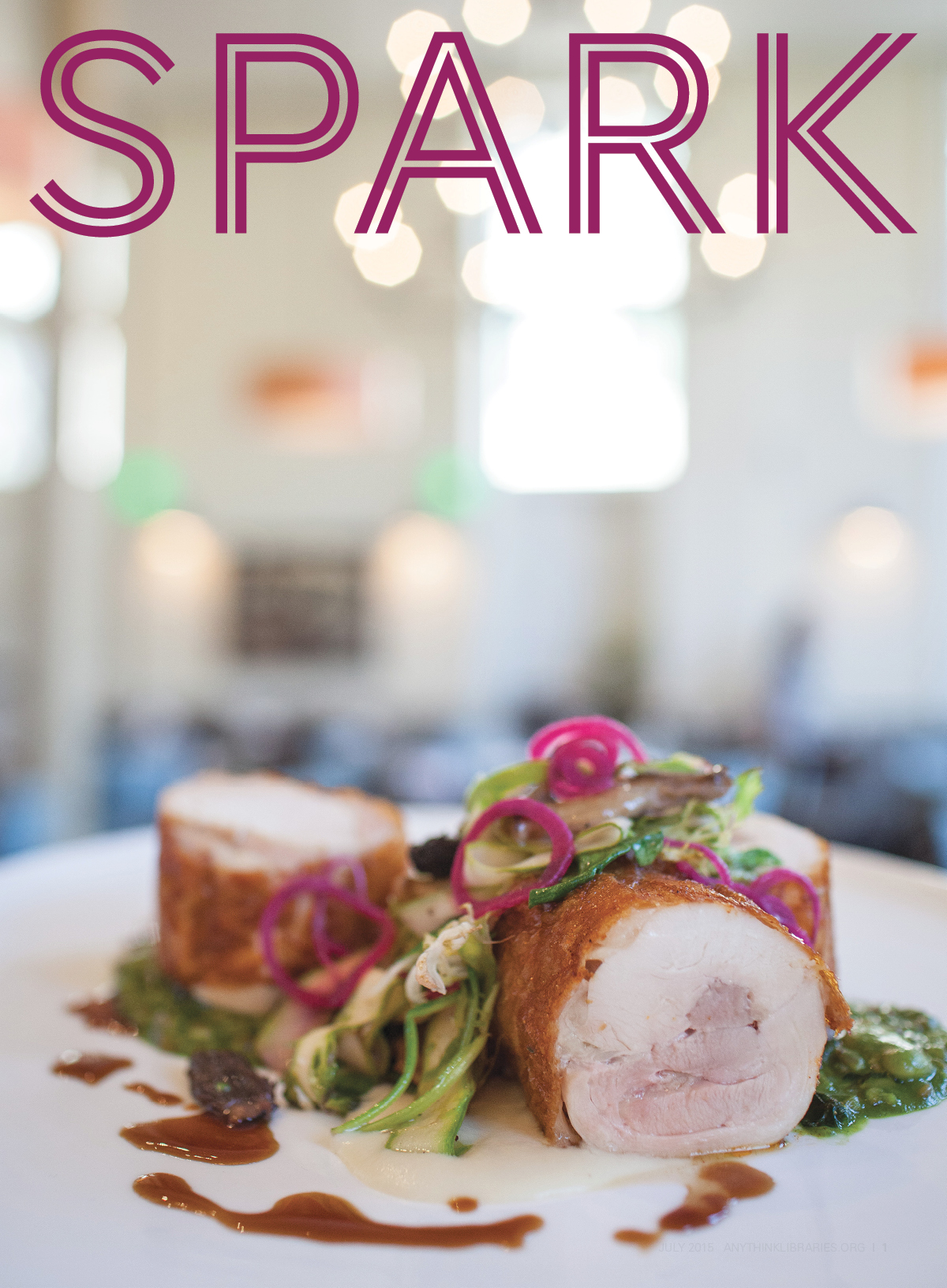

The Denver Poor Farm

The Denver Poor Farm

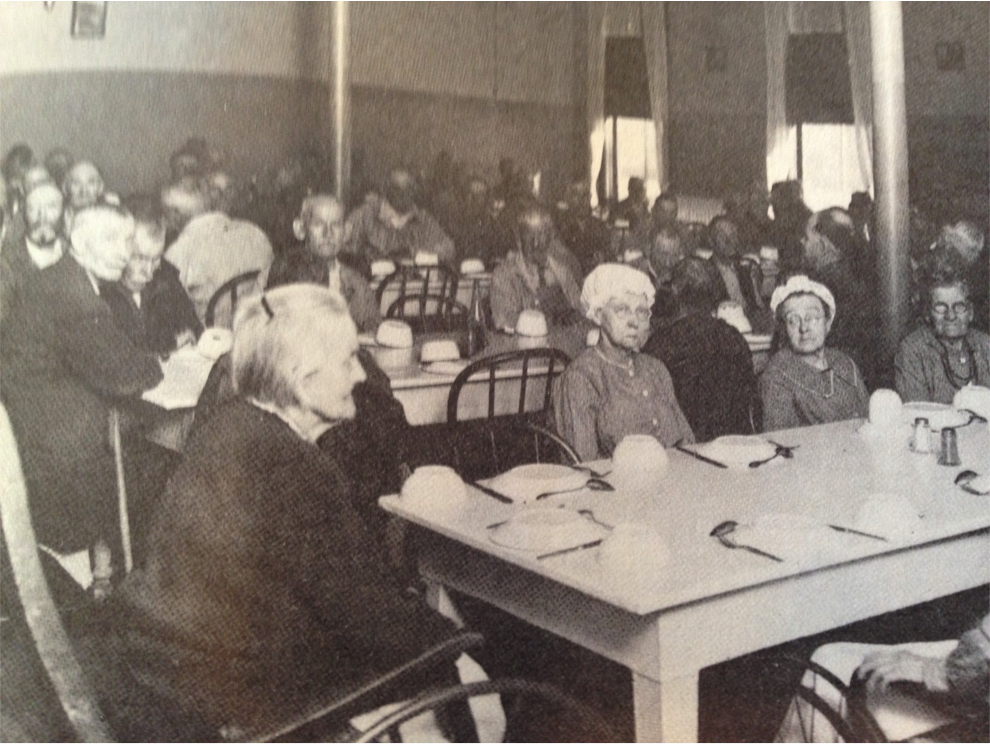

Near 128th Avenue and Riverdale Road in Brighton, Colo., sits one of Adams County’s community focal points, the Adams County Regional Park & Fairgrounds – a center for rodeos, fairs and concerts. But before the land was used for family gatherings and entertainment, it was home to an entirely different group of individuals – the poor and indigent of Denver.

In 1898, the City of Denver purchased 350 acres of what is now the regional park to serve as an area to send indigent patients from Denver General hospital, creating what would become known as the Denver Poor Farm. Since no public welfare system existed until 1933, Denver officials used the Denver Poor Farm for five decades to relocate some of the city’s less fortunate residents. With a farm, infirmary and residential housing, the land was meant to help provide a place for individuals to work and improve their lives.

Despite those intentions, the Denver Poor Farm saw its fair share of troubles for decades, marked by unsanitary conditions, crime and a 1911 outbreak of tuberculosis. According to Albert Foos, a Brighton resident who grew up at the farm with his family, the Denver Poor Farm took a turn for the better when Harold Lascelles, a former agricultural extension agent, took over as farm superintendent in 1937. Lascelles helped transform the Denver Poor Farm into a self-sustaining and at times even profitable farm, which included cattle, pigs, chickens, gardens and one of the finest dairy herds in the state. The dairy aspect of the farm was so successful, in fact, that the Denver Poor Farm won the Progressive Breeders Award of the Holstein-Friesian Association of America four times.

“It became a very profitable location,” notes Debra Bullock, secretary and treasurer of the Commerce City Historical Society. “It was very important in the community because of how much they were farming, which fed the farm’s residents. They also gave [extra] food back to Denver General to help feed patients there.”

In conjunction with the farm’s sustainable success, its roughly 300 residents also enjoyed recreational activities. Foos recalls the farm as “a big happy family” where employees and residents worked together and enjoyed social activities like horseshoes and cards.

Despite the turnaround, the Denver Poor Farm was finally dismantled in 1952, when Denver mayor J. Quigg Newton ordered its closure. The order was met with controversy, as local residents and politicians speculated its potential future and uses for helping community members in need. By 1959, the Denver Poor Farm was sold to Adams County under the conditions that it be used as a golf course, fairgrounds, race track and recreational park, serving the next generation of Adams County residents.

From internment camp to farm life

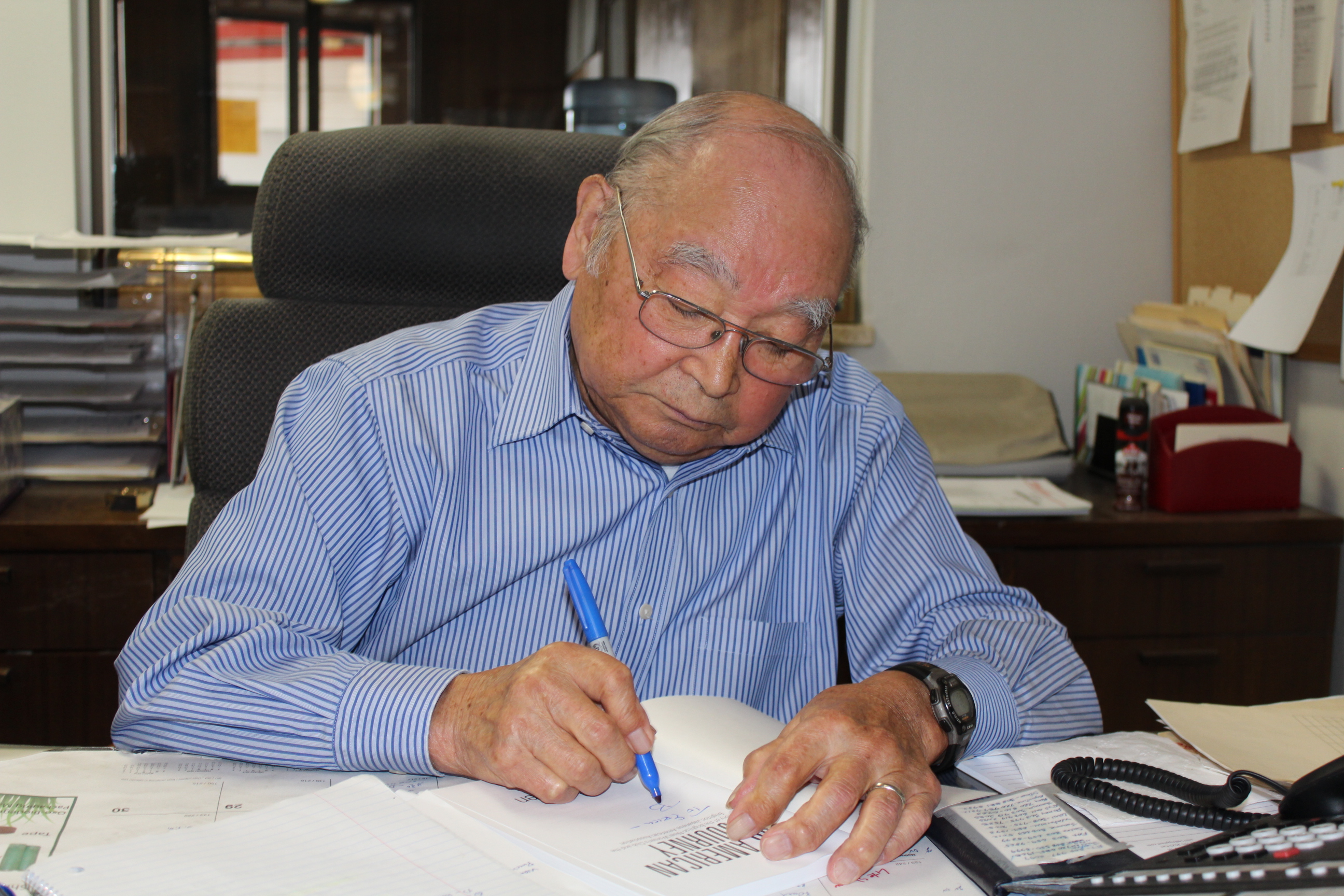

Just down the road from the Adams County Regional Park & Fairgrounds, Bob Sakata takes a seat in the office headquarters of Sakata Farms. He shows off his desk calendar, filled with tasks and meetings. At age 90, he shows no signs of slowing down.

Over the past 70 years, Sakata has grown his farm from its original 40-acre swath in Brighton to 2,500 acres that stretches across Adams and Weld counties, yielding produce such as sweet corn, cabbage, broccoli and onions. Farming comes naturally to Sakata, who grew up on a 10-acre farm in California. But his journey from California to Colorado wasn’t without tribulation.

In 1942, just months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Executive Order 9066, sanctioning the removal and incarceration of Japanese-Americans on the West Coast to designated internment camps. This same year, Sakata and his family were relocated to a camp in Topaz, Utah. After his release, Sakata came directly to Adams County, with the hope of starting over with his own farm.

The choice to farm in Colorado was a clear one. Sakata came specifically to the state because of Gov. Ralph Carr, one of the few politicians at the time to publicly decry the Japanese internment camps. Carr was outspoken about defending Japanese-American rights, and urged Coloradans to welcome them to the state, a stance that many speculate cost him his political career. Sakata expresses a strong appreciation for Gov. Carr, and even recognizes a silver lining in his imprisonment.

“What I went through [in the internment camp] was unconstitutional,” he states. “But I have no remorse. I look back as if it was a blessing in disguise. I would have never settled in Colorado and seen a bright future and experienced the good fortunes of American democracy.”

And Sakata’s future was certainly bright. He’s credited with founding and growing one of Adams County’s most successful farming operations. He was appointed to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s commodity credit advisory board. Sakata and his wife were also instrumental in founding the Brighton Community Hospital. In 1994, the Emperor and Empress of Japan paid Sakata Farms a visit during a rare trip to the United States.

Part of the reason for this prosperity is his ability to take risks and forever keep working toward new goals. He also is quick to credit his wife, Joanna, and his faith.

“I believe in perseverance,” Sakata says. “The failures I’ve experienced brought me to better days, and I refrain from using the word ‘successful.’ Success should never be final.”

Send your feedback and questions to ithink@anythinklibraries.org.