Building agricultural STEAM

Close your eyes and take a moment to imagine a farm. What do you see? Do you see drones flying above fields? What about driverless tractors carefully combing wheat fields? Is the farmer using a cell phone to operate her equipment?

While this might not be the first image that pops in your head, the face of modern agriculture is changing rapidly to be on the forefront of technology innovation. Here, we explore some of the ways in which STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics) is embedded in the lives and skillsets of modern agricultural communities.

Science

Science

Whether it’s livestock management or soil ecology, advanced knowledge of biology is intrinsic to any farming operation. As a result, agricultural communities are helping to advance public knowledge and research through their experiments and experiences. In Adams County, for example, Colorado State University (CSU) Extension works with farmers directly on things like unbiased onion variety research, a project trial that’s been underway for more than 30 years.

“What we’re looking at is a good environmental fit of onion varieties that are out there in the world,” says Dr. Thaddeus Gourd, CSU-Extension director and agricultural agent. “We plant them here to figure out which work best for Adams and Weld counties.”

Research like this not only leads to learning more about crops and their ideal environments, but can also help cut back on the use of pesticides in farming and increase yields. When testing a crop’s viability in a particular environment, project managers take into account things like resistance to plant pathogens and insects. Through detailed assessments, a specific varietal trait might surface that reduces the need for pesticides as a whole.

Gourd also points to local beekeeping efforts as “biology at its best.” Adams County Extension is currently working with local beekeeping groups like the Brighton Bee Club to test three different hive designs. Results from these tests will help to determine not only which designs work best for the bees, but which hives might be more accessible to the average backyard gardener interested in bees. Increasing interest in backyard beekeeping helps protect and increase the number of pollinators in the area, helping to enhance our overall ecosystem.

Technology

Technology

“Being 57, I missed the video game era,” says Colorado farmer Tim Brown with a laugh. “So now I’m just learning it. It’s not that hard – I’ve only had three major crashes.”

Brown, whose farm includes 7,000 acres of wheat in Limon, Colo., is referring to one of his latest gadgets: a drone. Though sometimes contentious, commercial use of drones is increasing across the globe for applications like package delivery and aerial media. For farmers, drones are becoming a commonplace tool for analyzing crops and properties in unprecedented ways. Take, for example, corn stalks which often grow to be over 8 feet tall.

“The options are just limitless,” notes Brown. “I’ve got a neighbor with corn, and in the cornfields they’re using drones a lot because they can see above the corn where we can’t. Corn is tall – how will you see above if you have a dry spot or see a place that needs more nutrients?”

Brown flies the drone using his cell phone, connected through a WiFi hub created by the drone itself. Though he primarily uses it to survey his land, he notes there a number of other ways that farmers are using drones – including things like the collection of geospatial data, access to dilapidated buildings, crop spraying, and high-spectral imaging for targeted fertilizing.

“I was the farmer with the big hat and the overalls, but I’ve been involved with new technology for a while,” says Brown. “I told my dad, ‘Either we get in or we get out, because we’re missing the boat.’”

Engineering

Engineering

As the tools that farmers use change, so do the needs of individual farmers. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the average American farmer is now over age 58. As technology steps in to help advance farming practice to include things like drones and driverless tractors, it’s also working to help the individuals out in the field.

For 25 years, the National AgrAbility Project has been working to improve the quality of life for people in agriculture who have some kind of disability or functional limitation. The organization, sponsored by the USDA, began as a project at Purdue University in response to a request from a specific individual. After suffering a spinal cord injury from a vehicular accident, this farmer was looking for a way to get back in his tractor. The university’s extension safety specialist worked with students to develop a solution to fit his specific situation, leading to the full development of AgrAbility. Today, the organization helps to serve a wide variety of individual needs.

“We deal with all kinds of disability – and disability is kind of a misleading term because people have preconceived notions of what that means,” says Paul Jones, program manager for AgrAbility. “But it’s any kind of a functional limitation – everything from arthritis to amputation to spinal cord injury, mental or behavioral health problems, chronic diseases, MS or heart disease. And we deal with the whole spectrum of agriculture, from traditional crop farming and livestock production all the way to hydroponics and organic produce and aquaculture.”

AgrAbility makes many recommendations that use already-existing products to address some of their most common requests, like arthritis. But for more complicated or specific cases, engineering students will often put their heads together to think of how a farming tool might be redesigned.

“Farmers themselves are quite ingenious, and a lot of them come up with their own solutions,” says Jones. “Many of the AgrAbility projects are housed in engineering departments. Usually, the engineering students have to complete some kind of senior project, and that’s another way to get ideas fabricated.”

Art

Art

Artist Stan Herd is no stranger to farm life. Growing up on a farm, he learned to drive a tractor at age 11. But even before that, at age 8 or 9, Herd considered himself an artist.

“My parents were very supportive of my artistic development and paid hard-earned money for a subscription art school that came in the mail,” says Herd.

The mail-order lessons paid off. Today, Herd is an internationally acclaimed artist who uses the land as a platform to help spark conversations about culture, the environment and mankind’s relationship with the earth. In 1981, he designed and created a 160-acre portrait of Kiowa Chief Satana in Kansas. Since this first monumental piece, he’s earned the title of the “Father of Crop Art” by creating 35 earthworks across the globe.

The process for creating these pieces requires both artistry and the ability to work the land. First, Herd will survey a specific site for soil, vegetation, planting possibilities, water issues and air traffic patterns. With these considerations in mind, he then sketches a field drawing for a piece of artwork he thinks will reflect the site. Then, it’s on to the fieldwork.

“I survey the field and then begin to etch the initial image into the ground with a weedeater, mower or small tractor and one bottom plow,” he says. “Then I try to fly over and photograph the work to see if it comports to my sketch. After that, it is a matter of planting or subtracting vegetation to complete the image, along with the possible addition of flowers, mulch, sand and other organic and non-organic materials.”

Herd finds inspiration in both sustainability and community building. His current project is a 4-acre piece called “Young Woman of Brazil” in Sao Paulo, Brazil. “Young Woman” is a work of particular cultural significance for Herd, a celebration of the country’s embrace of women’s issues and its renewed focus on impoverished areas. Working with other organizations, Herd’s “Young Woman” hopes to promote green spaces and gardens for young people in the favelas (urban slums) of Brazil.

Mathematics

Mathematics

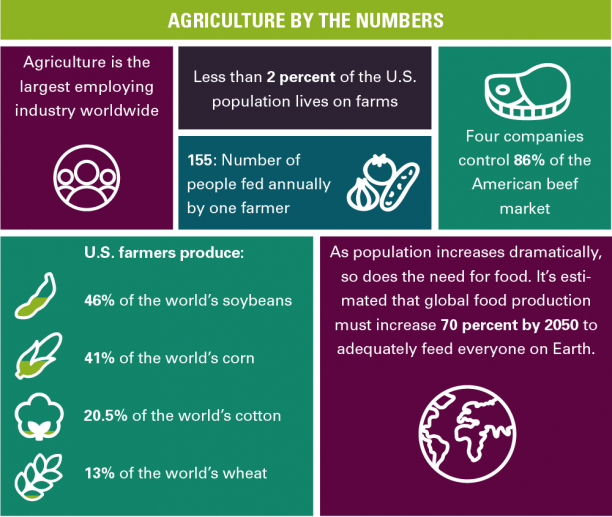

“Agriculture is not crop production as popular belief holds – it’s the production of food and fiber from the world’s land and waters. Without agriculture it is not possible to have a city, stock market, banks, university, church or army. Agriculture is the foundation of civilization and any stable economy.” –Allan Savory, Zimbabwean ecologist

You might not think about farmers holding business degrees, but the mathematical and economic requirements for a degree in agricultural science are many. To really understand the business of agriculture, one must understand the complex economics involved with operating a farm of any size. It can include everything from understanding basic ratios for successful crop planting or as complex as understanding the import/export markets and subsidies.

Sources: Bayer Crop Science U.S., Farm Bill Hackathon, USDA, American Farm Bureu, Worldbank.org, FAO.org

Send your questions or feedback to ithink@anythinklibraries.org or post in the comments below.